Before I was into all this stuff, I used to get 2-3 colds or flu infections per year, mostly in the winter. Now I rarely get them at all, and if I do, they are so mild I barely notice them. I don’t think there is anything especially amazing about my inherent immunity – it comes down to the products I take. I avoid milk products in the main as they are extremely mucous forming and contribute to catarrhal states, and I take quite a few supplements. But I think my rare contracting of winter viral infections primarily comes down to three core immune supporting products, and if you take them, you will get far fewer, if any winter sniffles too. So here we go with my tips for a healthy immune system all winter.

First take liquid oxygen – Vitamin ‘O’

Trying to be healthy whilst your body is improperly oxygenated is rather like trying to build a house on a swamp. In my opinion, optimal oxygenation is foundational to good health, but especially for warding off winter viruses bacterial and fungal infection. In this newsletter, I can’t go into the level of detail that Ed “Mr Oxygen” McCabe goes into in his seminal 650 page book “Flood Your Body With Oxygen” (you can buy it on Amazon though). All I will say is that taking any of our liquid oxygen products will do wonders for keeping cold’s, flu’s and other virus’s at bay, as well as help you inhibit those candida overgrowth and other dysbiotic micro-organisms that make a nuisance of themselves with so many of us. It’s impossible to say which of the four rival brands we provide is the “best” one – you might as well as ask me which is the “best” variety of apple, or which is the “prettiest” flower. Individual results do vary, and it is possible that if you try more than one, that one will work better for you than another one. However they all aim to do the same thing, which is flood the body with oxygen. Take the oxygen on ongoing basis – not just a few weeks – and countless health benefits will arise including the inhibition of winter time viremia.

Trying to be healthy whilst your body is improperly oxygenated is rather like trying to build a house on a swamp. In my opinion, optimal oxygenation is foundational to good health, but especially for warding off winter viruses bacterial and fungal infection. In this newsletter, I can’t go into the level of detail that Ed “Mr Oxygen” McCabe goes into in his seminal 650 page book “Flood Your Body With Oxygen” (you can buy it on Amazon though). All I will say is that taking any of our liquid oxygen products will do wonders for keeping cold’s, flu’s and other virus’s at bay, as well as help you inhibit those candida overgrowth and other dysbiotic micro-organisms that make a nuisance of themselves with so many of us. It’s impossible to say which of the four rival brands we provide is the “best” one – you might as well as ask me which is the “best” variety of apple, or which is the “prettiest” flower. Individual results do vary, and it is possible that if you try more than one, that one will work better for you than another one. However they all aim to do the same thing, which is flood the body with oxygen. Take the oxygen on ongoing basis – not just a few weeks – and countless health benefits will arise including the inhibition of winter time viremia.

A word of warning

Those that dabble do not get good results. This seems to happen particularly frequently with the liquid oxygen products for some reason. So don’t waste your time phoning us to tell us they didn’t work, only to then mention “Well actually, I kept forgetting to take it” or “I took it now and then”. It’s amazing how many people tell us it “didn’t work” when the reality was that they were messing about with it, and it never stood a chance of working.

Second, take Vitamin C – foundational immune support.

After all the the thousands of papers published on the benefits of therapeutic dosages (i.e… at least 1000mg per day) of Vitamin C over the last 50 years for a healthy immune system, it’s quite amazing that some of the more narrow minded doctors and scientists, are still arguing with us over this one. Like the smoking question, where naturopaths were warning the public that smoking was dangerous as far back as Victorian times, while the conventional medical profession looked on and sneered for literally 100 years, it is quite obvious they have completely lost this argument. So I am going to state here very clearly that I think that more or less everyone benefits from Vitamin C supplementation – beyond what they get in their diet.

How does Vitamin C support the immune system and reduce winter colds and flu?

It does this in several ways, including the boosting of the levels and activity of interferons (antiviral proteins), B-lymphocytes (which produce antibodies), T-lymphocytes (which attack invading organisms directly), or complement it (through an enzymic system that attacks bacteria and viruses). Enhanced T-Lymphocyte function probably results at least partially from Vitamin C’s action in raising prostaglandin E1 levels.

Vitamin C is also a powerful antioxidant nutrient, which means that it can protect us against toxins produced in the body called free radicals. These are implicated as being involved in increased risks of cataracts, arthritis, atherosclerosis, premature aging, and several other more serious pathological states.

Which Vitamin C and how much?

For optimal health, I believe in taking Vitamin C the whole year,  without any breaks at all. In the summer 1g (1000mg) per day is enough. In the winter, I recommend 2-3g per day for those whose immune systems are vulnerable. If you are following all the advice in this newsletter and still get a cold (which is much less probable), take 1g every couple of hours. We well quite a few Vitamin C products, and all of them will do the job, but when asked, my opinion is that the best one we provide is our Tapioca Vitamin C (formerly Ultra Pure Vitamin C) 1000mg 90 caps.

without any breaks at all. In the summer 1g (1000mg) per day is enough. In the winter, I recommend 2-3g per day for those whose immune systems are vulnerable. If you are following all the advice in this newsletter and still get a cold (which is much less probable), take 1g every couple of hours. We well quite a few Vitamin C products, and all of them will do the job, but when asked, my opinion is that the best one we provide is our Tapioca Vitamin C (formerly Ultra Pure Vitamin C) 1000mg 90 caps.

Warning

It’s best to take Vitamin C a couple of hours away from any of our liquid oxygen products for optimal results.

Third, take Vitamin D – the sunshine Vitamin

Vitamin D is a vital nutrient for optimal immune function, as shown in study after study. It is primarily sourced from the reaction between ultra violet light from the sun and cholesterol in the skin (yes, cholesterol isn’t all bad, in fact you would be dead without some presence of this substance in your body). In the days when we enjoyed outdoor agrarian or hunter gatherer lifestyles,we wouldn’t have as didn’t badly for uptake for vitamin D as today. In my opinion most people today are vitamin D deficient in winter, and research seems to be demonstrating that this is one of the big causes of increased risks of getting colds and flu’s.

Even conventional medicine is largely on our side on the deficency question. On the NHS web site, surprisingly, it states that ” A 2007 survey estimated that around 50% of all adults have some degree of vitamin D deficiency.” An American study reported that 32 percent of children and adults throughout the US were vitamin D deficient. However we think both of these are gross underestimates because the recommended minimal levels of Vitamin D that these surveys are based on are ludicrously low.

We think that Dr Joseph Mercola, a conventionally trained doctor who has ‘gone natural’ is getting much closer to the truth where he estimates that 95% of elderly people are vitamin D deficient “not only because they tend to spend a lot of time indoors but also because they produce less in response to sun exposure (a person over the age of 70 produces about 30 percent less vitamin D than a younger person with the same sun exposure)”. However I would go even further by saying in my opinion, if you live in northern Europe and work indoors, your vitamin D levels are probably significantly sub-optimal for ideal immune function, almost all the time but more so in winter, no matter what age you are.

Vitamin D and colds or flu

In the largest and most nationally representative studof its kind to date, involving about 19,000 Americans, people with the lowest vitamin D levels reported having significantly more recent colds or cases of the flu — and the risk was even greater for those with chronic respiratory disorders like asthma. (Reported in the The Journal Of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine February 3, 2009; 169(4) 384-390) At least five additional studies also show an inverse association between lower respiratory tract infections and vitamin D levels. Clearly Vitamin D is important for a healthy immune system.

Which Vitamin D product to take?

Almost any Vitamin D product would be better than nothing, and our full list of such products is found here. However vitamin D works synergistically with Vitamin K2 (this is NOT the same as Vitamin K1, which is derived from green leafy vegetables) for its benefits to be most efficiently realised. For this reason, of the various Vitamin D products we provide, I believe the best one, , is Vitamin D3 5,000iu with Vitamin K2 – 90 tablets. This also happens to be our highest strength one. The government RDA for Vitamin D is 200iu per day, which in my view is ridiculously low. If you are serious about boosting your immune system, rather than taking the minimum amount to avoid dropping dead, you need to take one per day of this product. (Children can take it with less frequency, to get to an equivalent amount relative to their weight compared to an adult).

Almost any Vitamin D product would be better than nothing, and our full list of such products is found here. However vitamin D works synergistically with Vitamin K2 (this is NOT the same as Vitamin K1, which is derived from green leafy vegetables) for its benefits to be most efficiently realised. For this reason, of the various Vitamin D products we provide, I believe the best one, , is Vitamin D3 5,000iu with Vitamin K2 – 90 tablets. This also happens to be our highest strength one. The government RDA for Vitamin D is 200iu per day, which in my view is ridiculously low. If you are serious about boosting your immune system, rather than taking the minimum amount to avoid dropping dead, you need to take one per day of this product. (Children can take it with less frequency, to get to an equivalent amount relative to their weight compared to an adult).

Is Vitamin D safe?

It has been claimed that taking Vitamin D is potentially toxic, but is this really true?

It has been claimed that taking Vitamin D is potentially toxic, but is this really true?

Vitamin D is normally measured in i.u.’s which stands for International Units.

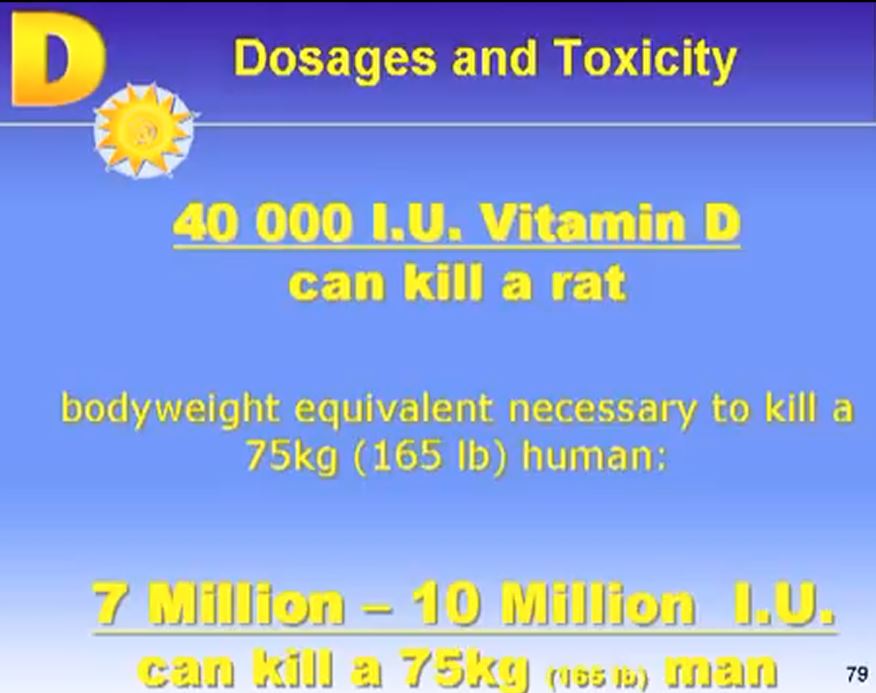

Perhaps the screen shot on the left from a lecture I watched recently on Vitamin D on YouTube will help you make up your mind. Remember our highest strength vitamin D product contains 5,000 i.u. per tablet – not 7 million i.u.!

It has also been suggested that taking over 40,000 units per day for more than three months is potentially toxic, but even this seems to be an exaggeration. I have seen other research showing that Vitamin D was not shown to be toxic even on as high a dosage as 75,000iu’s taken every day on a long term basis. It also seems illogical because the body can naturally produce up to 30,000i.u’s in the summer just from 30 minutes of sunbathing!In the winter time in the UK, the sun’s angle to the horizon is too low to produce Vitamin D even if you were outside all day and the sunning is shining. Nonetheless I do not recommend taking amounts higher than 5-000 to 10,000i.u’s per day, which still keeps things vastly lower than any estimates of the toxicity threshold.

In another video found on YouTube, Dr. Kate Rheaume-Bleue claims that vitamin D when combined with K2 has no known toxicity on any dosage. That’s because vitamin D ‘toxicity’ is not really toxicity at all, but an increased requirement for Vitamin K2 when Vitamin D is taken. ‘Toxicity’ occurs if there isn’t enough Vitamin K2 in the body for Vitamin D to function appropriately in the body – and even then you would need to take a ludicrous dosage for this to occur.

The big three for a healthy immune system – Liquid Oxygen – Vitamin C – Vitamin D

So those are my big three. It is true that many other products can also be used to prevent or shorten a cold or flu – such Colloidal Silver, Zinc, Selenium, Cat’ Claw, Pau d’Arco (Lapacho), Echinacea Cold Flu Relief, and quite a few others, found here. As always I have only scratched the surface of what I would like to say, but if you follow these steps, I am confident you will get a lot less colds and flu’s this winter.

The next newsletter is going to on natural pain relief…

Mark G. Lester

Director – The Finchley Clinic Ltd

www.thefinchleyclinic.com

Trying to be healthy whilst your body is improperly oxygenated is rather like trying to build a house on a swamp. In my opinion, optimal oxygenation is foundational to good health, but especially for warding off winter viruses bacterial and fungal infection. In this newsletter, I can’t go into the level of detail that Ed “Mr Oxygen” McCabe goes into in his seminal 650 page book “Flood Your Body With Oxygen” (you can buy it on Amazon though). All I will say is that taking

Trying to be healthy whilst your body is improperly oxygenated is rather like trying to build a house on a swamp. In my opinion, optimal oxygenation is foundational to good health, but especially for warding off winter viruses bacterial and fungal infection. In this newsletter, I can’t go into the level of detail that Ed “Mr Oxygen” McCabe goes into in his seminal 650 page book “Flood Your Body With Oxygen” (you can buy it on Amazon though). All I will say is that taking  without any breaks at all. In the summer 1g (1000mg) per day is enough. In the winter, I recommend 2-3g per day for those whose immune systems are vulnerable. If you are following all the advice in this newsletter and still get a cold (which is much less probable), take 1g every couple of hours. We well quite a few Vitamin C products, and all of them will do the job, but when asked, my opinion is that the best one we provide is our

without any breaks at all. In the summer 1g (1000mg) per day is enough. In the winter, I recommend 2-3g per day for those whose immune systems are vulnerable. If you are following all the advice in this newsletter and still get a cold (which is much less probable), take 1g every couple of hours. We well quite a few Vitamin C products, and all of them will do the job, but when asked, my opinion is that the best one we provide is our  Almost any Vitamin D product would be better than nothing, and our full list of such products is found

Almost any Vitamin D product would be better than nothing, and our full list of such products is found

Zinc has also been shown to be useful in many studies both for preventing colds and supporting the immune system generally. We provide a number of zinc products, but the one I personally use is

Zinc has also been shown to be useful in many studies both for preventing colds and supporting the immune system generally. We provide a number of zinc products, but the one I personally use is  Thirdly, take Vitamin D, which is incredibly important for the entire immune system. Unfortunately, almost everyone living in Norther Europe is Vitamin D deficient at this time of year, and dark skinned people who who absorb vitamin D much more slowly than white Europeans (from the reaction between ultra violet light from the sun on the skin and cholesterol), are nearly always Vitamin D deficient the entire year! The Recommended Daily Allowance for Vitamin D is a pitiful 200iu per day, but my opinion is that this is utter nonsense. In the summertime, 30 minutes exposure to the sun enables the body to produce 10,000-20,000iu’s per day – in other words up to 50 times more than the EU Recommended Daily Allowance. So why is the Daily Allowance so low? There are proposals incidentally, coming from the unelected wastes of taxpayers money know as the EU, ever influenced by the vested interests of big pharma to limit your the legal availability of Vitamin D supplements to the pathetic 200iu I just spoke about. Anyway, whilst this has not occurred, I recommend 1-2 tablets per day of

Thirdly, take Vitamin D, which is incredibly important for the entire immune system. Unfortunately, almost everyone living in Norther Europe is Vitamin D deficient at this time of year, and dark skinned people who who absorb vitamin D much more slowly than white Europeans (from the reaction between ultra violet light from the sun on the skin and cholesterol), are nearly always Vitamin D deficient the entire year! The Recommended Daily Allowance for Vitamin D is a pitiful 200iu per day, but my opinion is that this is utter nonsense. In the summertime, 30 minutes exposure to the sun enables the body to produce 10,000-20,000iu’s per day – in other words up to 50 times more than the EU Recommended Daily Allowance. So why is the Daily Allowance so low? There are proposals incidentally, coming from the unelected wastes of taxpayers money know as the EU, ever influenced by the vested interests of big pharma to limit your the legal availability of Vitamin D supplements to the pathetic 200iu I just spoke about. Anyway, whilst this has not occurred, I recommend 1-2 tablets per day of

If you haven’t already done this, all you have to do is visit our

If you haven’t already done this, all you have to do is visit our  Wishing Good Health To All Our Valued Customers.

Wishing Good Health To All Our Valued Customers.